Videographic research is as old as film. If we consider a succinct historical perspective, cinema was in the first instance silent, where the image was exclusively based on visuality and movement. In hindsight, we can acknowledge the evocative power of video already in the first-known productions. A founding event took place at the Salon Indien du Grand Café in Paris on December 28, 1895. Ten short films (each less than one minute) were featured by the Lumière Brothers, consisting in the initial milestone of commercial public film screening.

Here is a link gathering some of these pioneering filmmaking works by the Lumière Brothers: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4nj0vEO4Q6s

These earliest filmed sequences described various lifestyle activities, rituals, humorous and mundane interactions, such as workers exiting a factory, a baby eating, a gardener at work, etc. Beyond a mere description of ordinary events was a willingness to generate vivid reactions and blissful amazement. A famous case of film’s powerful affective capacities was the creation of an illusion of a steam train bustling right towards the camera – causing a wave of horror among spectators, imagining being swept away by the train.

In this PART II of our series of filmed introductions to videographic research, we will focus on unpacking the history of filmmaking in research as well as begin a discussion on future perspectives. (Part I available here.)

Despite the long history of filmmaking, scholarly use of videography as a research method has emerged only recently, for example, in the field of consumer and marketing research (Belk and Kozinets, 2005; Belk et al. 2018; Rokka and Hietanen 2018; Veer, 2014). There is an evident increase in attempts in developing video-based approaches across disciplinary fields spurred not least by ease of access, lower costs, and availability of video production tools. But as scholars have been quick to point out, we still lack ontological, epistemological and methodological considerations as well as vocabulary so as to address video and what it may become.

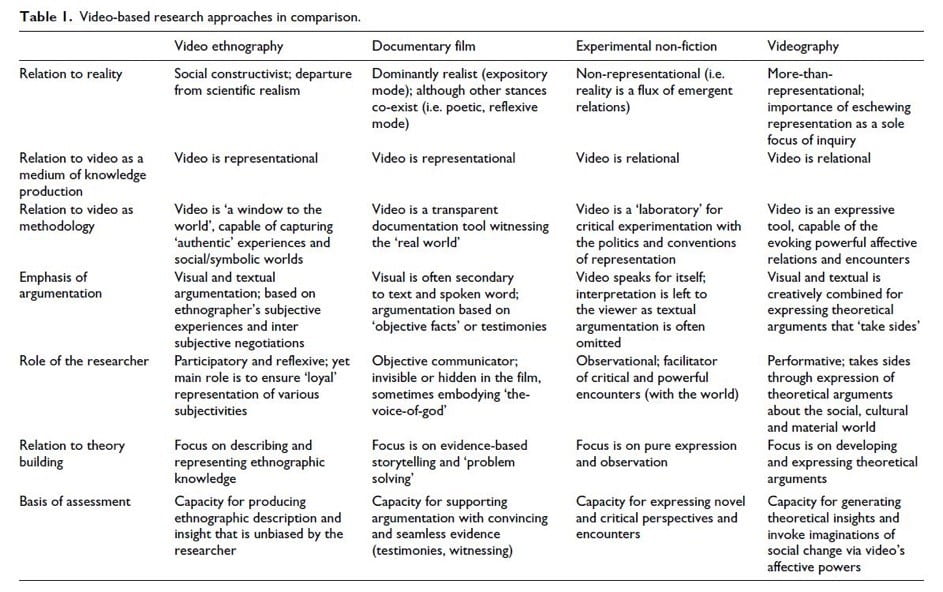

The lexical field already requires more precision. The concept of ‘videography’ has thus far been employed very loosely to refer to nearly any form of academic film production. Can any kind of video footage be called videographic research and what about different genres, modes, and styles? We find it is useful to examine the history of distinct filmmaking practices in this regard (see Table 1, Rokka and Hietanen 2018, p. 109).

First, videography shares similarities but can also be distinguished from visual and video ethnography used by anthropologists, described well by Pink (2007) as “video footage that is of ethnographic interest or is used to represent ethnographic knowledge” (p. 169). This framing allows the inclusion of all formats and conventions as long as it accommodates with ethnographic requirements.

Another distinctive practice towards film can be found in documentary filmmaking (Nicholls 2001), which also harbours several kinds of creative “modes” of video-based representation including, for example, reflexive, observational, and collaborative films. These approaches stand out in that while there is an interest in knowledge production and argumentation. Yet, there is less emphasis and focus on explicit theorizing which would build on existing theories or literature.

Lastly, the approach that is perhaps closest to pure artistic expression is ‘experimental non-fiction film’ (Russell 1999). This filmmaking tradition seeks to actively rethink conventional uses of video footage and cinematography while addressing acute societal issues. These films have been described as avant-garde engagements that conjointly blend social theory and unexplored aesthetics to challenge common social-cultural views. Distinctively from the ethnographic and documentary films, these approaches also treat video more as “relational” rather than “representational”: a sort of laboratory for critical experimentation with the politics and conventions of video representation.

Hence, it is important to recognize the heterogeneity in (historical) approaches and also learn from them. Moving forward, we suggest a suitable conception for videographic research as the “theoretical argumentation and elaboration through moving image and sound” (Rokka and Hietanen 2018, p.113) to be relevant. This notions considers videographic research also as a « performance » (Seregina 2018) through which the researcher engages and re-envisions the world, and in doing so employs video-based evidence in its expression and articulation.

Yet, much more needs to be done in elaborating a new vocabulary for thinking and talking about research in this way. This includes, as explained in the table, considerations about how the researcher considers and reveals her/himself to be an actor in the videographic productions.

The following links seek to elaborate on these points, shedding some further light on the history and future of videography. More will follow soon.

Session 4: History of Videographic Research

Session 5: Future of Videographic Research

References

Denzin, N.K. (1995) The Cinematic Society: The Voyeur’s Gaze. London: SAGE.

Belk, R.W. and Kozinets, R.V. (2005) Videography in marketing and consumer research. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 8(2): 128–141.

Belk, R.W., Caldwell, M., Devinney, T.M., Eckhardt, G.M., Henry, P., Kozinets, R.V. and Plakoyiannaki, E. (2018) Envisioning consumers: how videography can contribute to marketing knowledge, Journal of Marketing Management, 34 (5-6), 432-458.

Nichols, B. (2001) Introduction to Documentary. Bloomington, IN; Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press.

Pink, S. (2007) Doing Visual Ethnography. London: SAGE.

Rokka, J. and Hietanen, J. (2018) On positioning videography as a tool for theorizing, Recherche et Applications en Marketing (English edition), 33 (3), 106-121.

Russell, C. (1999) Experimental Ethnography: The Work of Film in the Age of Video. Durham, NC; London: Duke University Press.

Seregina, A. (2018) Engaging the audience through videography as a performance, Journal of Marketing Management, 34 (5-6), 518-535.

Veer, E. (2014) Ethnographic videography and filmmaking for consumer research. In: Bell E, Warren S and Schroeder J (eds) The Routledge Companion to Visual Organization. London: Routledge, pp. 214–226.

Commentaires récents