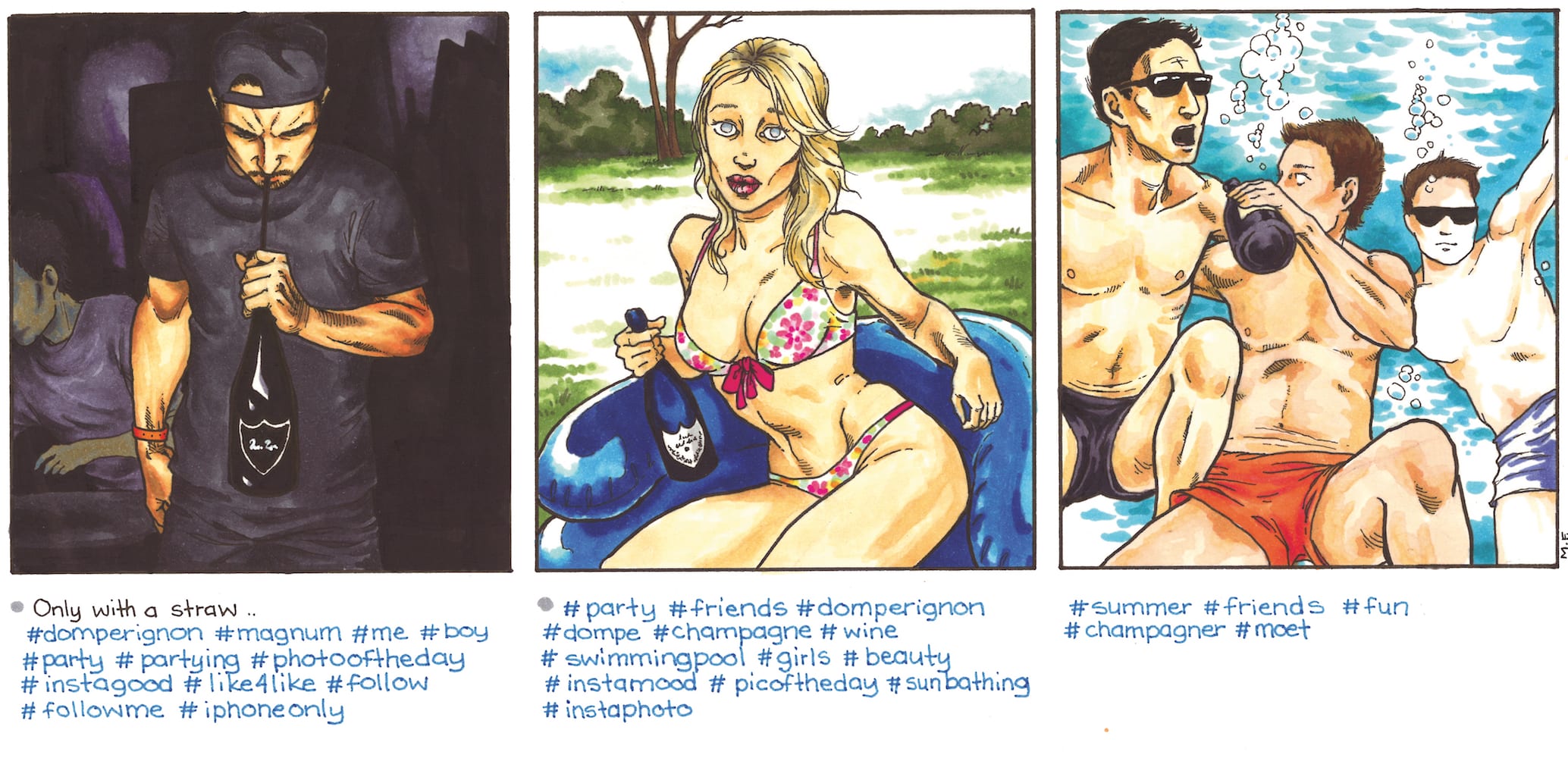

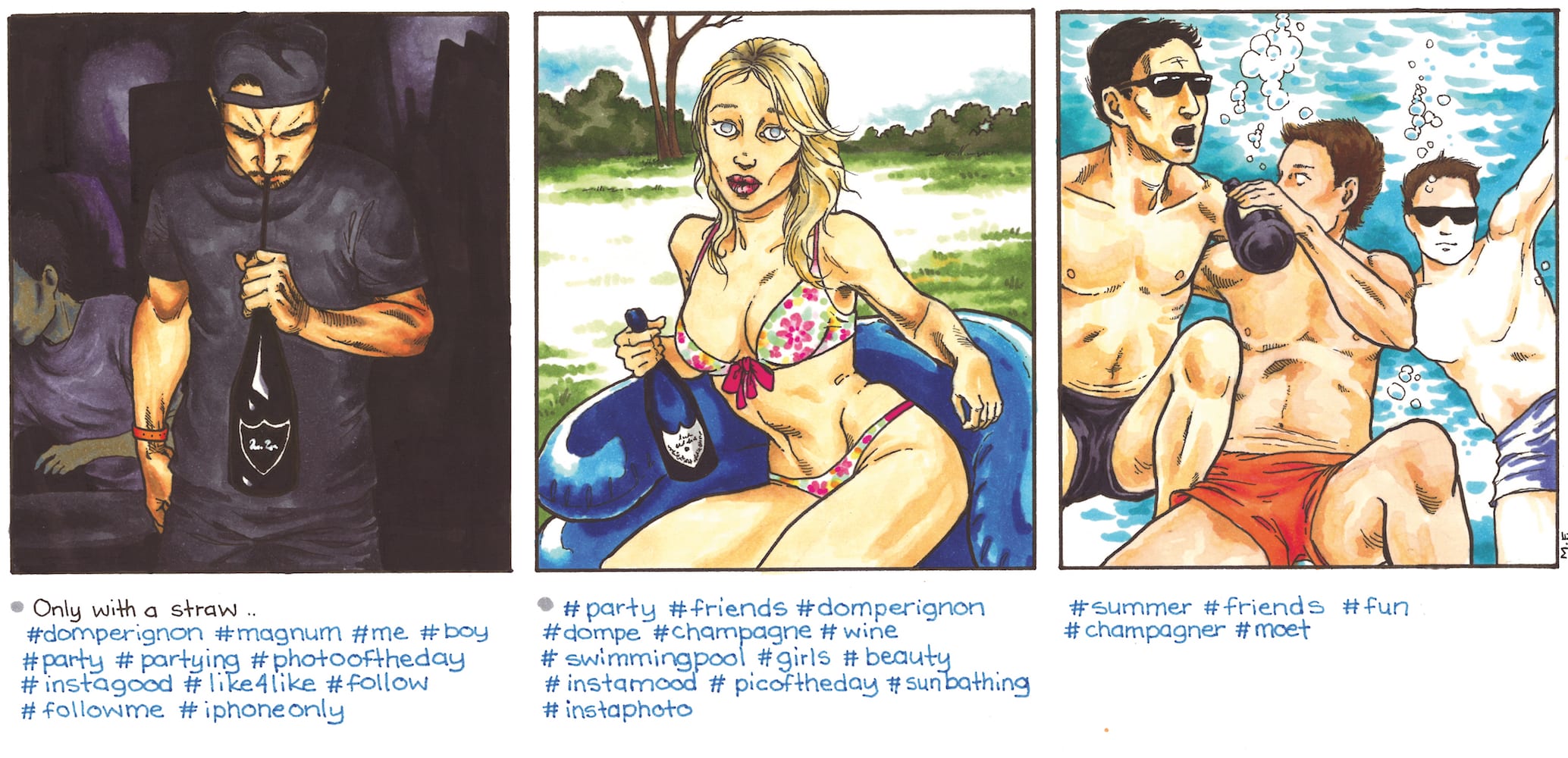

Brand selfies featuring champagne in Instagram (image by artist Maria Federley)

While self-portraiture is nearly as old as art itself, the photographic selfie emerged as a globally recognized phenomenon only recently, as a result of the rising “attention economy” and its growing appetite for likes, followers, retweets and fame. Google estimates that some 24 billion selfies were taken in a year via 200 million Google accounts alone in 2016, which signals that the phenomenon is far from being marginal. This reveals why selfies matter so much for marketers and brands: selfies have the capacity to catch and intrigue attention – the single most valuable marketing asset of today.

Selfies’ allure for attention

Recognizing this opportunity, companies and brands have turned the magnetic “power” of the selfie a key element of their marketing campaigns and social-media content strategies. Apple’s advertising images feature sleek youngsters snapping selfies of their romantic play, Nike has turned star footballer Neymar’s selfie obsession into art in their ads, GoPro and Turkish Airways showcase their products and services via selfies, and recently Tesco employed Augmented Reality application to allow their consumers to take selfies with favourite Frozen (Disney) characters.

Selfies have also been identified as an important “self-branding” practice. Driven by the quest for attentional capital in the forms of quantifiable likes, shares and followers, selfies have seduced celebrities and stars – not least the Kardashian family who currently dominates Instagram as the most popular family of all –, but equally rappers and gangsters, presidents and popes to use selfies as an important strategy for engaging their audiences. Yet selfies are not reserved for the elite but they can be found in nearly everyone’s social media pages. In this sense, social media enables “microcelebrity” – that is, when ordinary people mimic celebrities’ postings aimed to signal fame and attractiveness to others. Interestingly, this happens often via selfies taken with desirable brands and products, such as “unboxing” images of Louis Vuitton, Chanel, or Hennessy.

In addition to providing attention, the selfies matter for brands in at least two other important ways. I call these the “snapshot authenticity” and “brand co-creation”, I will turn to explain these notions in the following.

Snapshot Authenticity

The selfie phenomenon has important connections with the idea of self-portraits in fine arts that emerged in the 16th Century. Already classic works of artists such as Albrecht Dürer and Rembrandt, for example, featured paintings, engravings and drawings of the artist face-to-face with the spectator. These images often featured the artist “in action” in the artist’s studio, usually holding the pencils, brushes and colour palette in hand, in order to give the impression that the image was spontaneous and authentic in nature.

Similarly to self-portraits in fine arts, selfies share much in common with the visual genre called “snapshot aesthetic”, commonly in use in photography and commercial images. Snapshot relies on the authentic feeling of images snapped “on the go” of our daily lives. These casual, everyday images help us narrate and make sense of our selves but also communicate our existence to those around us.

Authenticity is precisely what brands seek to associate with in a world of hyper-competition. The selfies and snapshot aesthetic thus provide them with a powerful resource. Above all, it gives them an impression of candid and unfettered access to original expressions.

Brand meaning co-creation

At the same time, brands grow increasingly aware – and often uncomfortably so – that since selfies can virtually be taken by anyone, they also constitute a whole new form of brand meaning co-creation. For example, in my research I have shown that masses of ordinary people use “brand selfies” – in other words, selfies featuring recognizable brands either visibly or via hashtags – to express their identities as complex assemblages of things, objects and brands. This challenges the conventional marketing idea that it is the brand manager who defines and communicates the meanings to be associated with their brand.

In my research on the champagne brand Moët & Chandon, I found that about 20.000 brand selfies per month are posted by consumers themselves. While repeating some of the defining associations of this luxury brand – including the iconic bottle, glasses, wine and the famous bubbles – the selfies also reveal alternative constructions of the brand with new kinds of material and expressive elements. Instead of being focused on the brand, the selfies were systematically centred on the “self”, making the brand necessarily more peripheral. For example, the selfies had a tendency to include a collection of brands (40% of images), instead of a single brand. In addition, the presence of human bodies and identifiable faces break the brand’s singularity and gives it an often banalized expression.

In this way, selfies are also forcing the marketers to re-consider campaign strategies.

Conclusion

As reflected in the recent In Memory of Me exhibition in Paris, by artist Stéphane Simon, where selfies are turned into contemporary sculptures, it is not a far stretch to think how closely god-like sculptures, ancient modes of celebrity culture and fame, and contemporary selfie practices become intertwined with media, celebrities and branding. Selfies carve out and polish up identities, mould and cement brands, and also seed and embody fame.

Post by Joonas Rokka, Professor of Marketing, EMLYON Business School

Based on text originally published as:

Rokka, Joonas (2017) How selfies can build and destabilize brands, The Conversation